Case #12: Feeling a Little Yellow

Author: Michael Gottlieb, MD

Peer Reviewer: Navneet Cheema, MD

A 68 year old male with a history of severe osteoarthritis of his bilateral knees presents with generalized malaise and weakness. He was previously seen in a local free clinic three days prior and given “pain medication”. Yesterday, he had no appetite, felt nauseated, and vomited four times. Today, the nausea subsided, but he still felt ill, which prompted him to come to the ED. He recalls taking two “pain pills” every 2-3 hours because the pain was really bothering him. He does not recall the name of the medication. On physical exam, he is alert, in mild distress, appears jaundiced, and has mild RUQ tenderness to palpation. The remainder of his exam is normal.

Vitals: Temp: 98.0, HR: 92, RR: 14, BP: 132/84, O2 sat: 100% on RA

What is the most likely etiology of this patient’s presentation?

The combination of GI symptoms, jaundice, RUQ pain, and recent increased ingestion of “pain medications” (think NSAIDs, acetaminophen, aspirin, or opioids when given this clue) makes acetaminophen (APAP) toxicity the most likely diagnosis.

What is the typical clinical presentation one would expect to see in this patient?

Phase I (1-24 hours): GI symptoms (anorexia, nausea, vomiting).

Phase II (24-72 hours): “Latent” phase with resolution of GI symptoms and small elevation in liver enzymes.

Phase III (Days 3-4): Severe hepatotoxicity with recurrence of GI symptoms

Phase IV (After Day 5): Clinical recovery or multi-organ failure and death

What is the mechanism of injury in this toxicity?

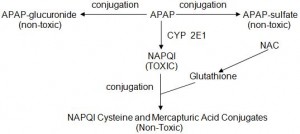

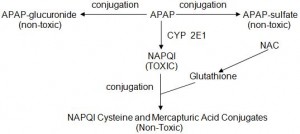

APAP is broken down via three mechanisms: glucuronidation, sulfonation, and enzymatic conversion to NAPQI (see below). Glucuronidation and sulfonation result in non-toxic APAP metabolites. In therapeutic APAP doses, the small amount of NAPQI produced, easily combines with glutathione to form non toxic metabolites. In overdose, the glucuronidation and sulfonation pathways become saturated resulting in a larger proportion of APAP being metabolized to NAPQI. Eventually the body depletes its store of glutathione and can no longer detoxify NAPQI. This results in liver injury and the clinical picture described previously. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) regenerates glutathione which is the rate-limiting step of NAPQI breakdown.

What is the initial treatment for this patient?

If acetaminophen toxicity is suspected, begin NAC. Dosing is as follows:

PO: 140 mg/kg Loading Dose, followed by 70 mg/kg Q 4 Hours x 17 doses

IV: 150 mg/kg Loading Dose, followed by 50 mg/kg over 4 hours, followed by 100 mg/kg over 16 hours

NAC should be continued until the labs normalize (specifically INR, bilirubin, AST/ALT), the acetaminophen level is undetectable, and the patient’s condition is improving. Newer literature supports tailoring the NAC to the patient, rather than following set time frames.

How would your management change if this were an acute ingestion?

If the patient presents shortly after ingestion (< 1 hour), consider giving activated charcoal (Adult: 50-100 g, Pediatrics: 1g/kg). Also, remember to plot the APAP level on the Rumack-Matthew nomogram to predict the likelihood of toxicity and need for treatment. The nomogram is NOT intended to be used for chronic ingestions or patients presenting >24 hours after ingestion.

What are the criteria for transplant in these patients?

King’s College Criteria for immediate referral for liver transplant:

1. pH < 7.30 or lactate > 3 mg/dL after full fluid resuscitation at 12 hours.

OR

2. INR > 6.5 (PTT > 100 sec) PLUS Creatinine > 3.4 mg/dL PLUS Grade 3 or 4 hepatic encephalopathy.

Of note, a Lactate > 3.5 mg/dL after fluid resuscitation, Phosphorus > 1.2 mmol/dL at 48 hours, and APACHE II score > 15 have also been shown to be predictive of the need for transplant.

References:

Bailey B, Amre DK, Gaudreault P. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to acetaminophen poisoning: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic criteria determining the need for liver transplantation. Crit Care Med. 2003 Jan;31(1):299-305.

Chun LJ, Tong MJ, Busuttil RW, et al. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and acute liver failure. J Clin Gastroenterol 43: 342, 2009.

Daly FF, Fountain JS, Murray L, et al. Guidelines for the management of paracetamol poisoning in Australia and New Zealand—explanation and elaboration. A consensus statement from clinical toxicologists consulting to the Australasian poisons information centres. Med J Aust 188: 296, 2008.

Dart RC, Rumack BH. Patient-tailored acetylcysteine administration. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Sep;50(3):280-1.

Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am 92: 761, 2008.

Green JL, Heard KJ, Reynolds KM, et al. Oral and Intravenous Acetylcysteine for Treatment of Acetaminophen Toxicity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. West J Emerg Med. 2013 May;14(3):218-26.

Rumack BH, Matthew H. Acetaminophen poisoning and toxicity. Pediatrics 55: 871, 1975.

Smilkstein MJ, Knapp GL, Kulig KW, et al. Efficacy of oral N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose. N Engl J Med 319: 1557, 1988.

Waring WS, Stephen AF, Malkowska AM, et al. Acute acetaminophen overdose is associated with dose-dependent hypokalaemia: a prospective study of 331 patients. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 102: 325, 2008.

Wolf SJ, Heard K, Sloan EP, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the management of patients presenting to the emergency department with acetaminophen overdose. Ann Emerg Med 50: 292, 2007.

Return to Case List